Nabokov’s Infernos

Schizomythology, promiscuous textuality, plagiary by anticipation

La mémoire de la littérature marche ainsi tout naturellement à reculons, chaque texte venant s’éclairer de la lecture d’autres qui lui sont pourtant postérieurs.

(Le Tellier 2006: 174).

§ 0. Introduction

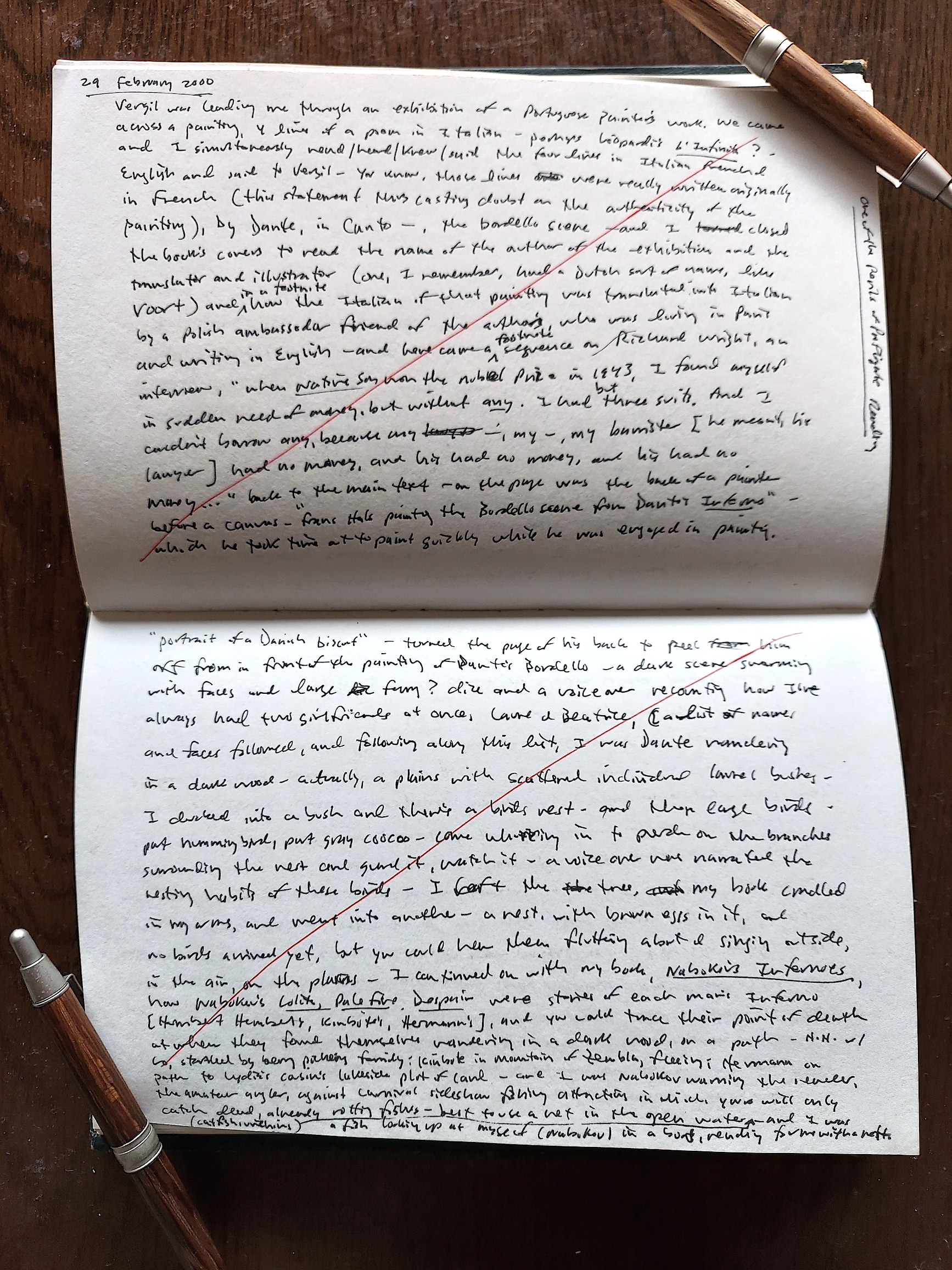

Nabokov’s Infernos begins with a dream I awoke from in Paris on the afternoon of February 29, 2000: — Vergil was leading me through an exhibition of a Portuguese painter’s work. We came across a painting, four lines of a poem in Italian — perhaps Leopardi’s L’Infinito? — and I simultaneously read/heard/knew/said the four lines in Italian, French, and English, and said to Vergil, “You know, those lines were really written originally in French” (this statement thus casting doubt on the authenticity of the painting) “by Dante, in Canto __, the bordello scene” — and I closed the book’s covers to read the name of the author of the exhibition and the translator and illustrator (one, I remember, had a Dutch sort of name, like Voort) and in a footnote how the Italian of that painting was translated into Italian by a Polish ambassador friend of the author’s who was living in Paris and writing in English — and here came a footnote sequence on Richard Wright, an interview: “When Native Son won the Nobel Prize in 1943, I found myself in sudden need of money, but without any. I had but three suits. And I couldn’t borrow any, because my —, my —, my barrister (he meant his lawyer) had no money, and his had no money, and his had no money...” back to the main text: On the page was the back of a painter before a canvas: “Frans Hals painting the Bordello scene from Dante’s Inferno” — which he took time out to paint quickly while he was engaged in painting “Portrait of a Danish Biscuit” — [I] turned the page of his back to peel him off from in front of the painting of Dante’s Bordello — a dark scene swarming with faces and large furry (?) dice and a voiceover recounting how I’ve always had two girlfriends at once, Laure and Beatrice (a list of names and faces followed), and following along this list, I was Dante wandering in a dark wood — actually, a plain with scattered individual laurel bushes. I ducked into a bush and there’s a birds nest — and those large birds, part hummingbird, part gray cuckoo, come whizzing in to perch on the branches surrounding the nest and guard it, watch it. A voiceover was narrating the nesting habits of these birds. I left the tree, my book cradled in my arms, and went into another. A nest, with brown eggs in it, with no birds arrived yet, but you could hear them fluttering about and singing outside, in the air, on the plains. I continued on with my book, Nabokov’s Infernos: how Nabokov’s Lolita, Pale Fire, and Despair were stories of each man’s Inferno [Humbert Humbert’s, Kinbote’s, Hermann’s],

and you could trace their point of death at when they found themselves wandering in a dark wood, on a path: H. H. with Lo, startled by berry picking family; Kinbote in mountains of Zembla, fleeing; Hermann on path to Lydia’s cousin’s lakeside plot of land — and I was Nabokov warning the reader, the amateur angler, against carnival sideshow fishing attractions in which you will only catch dead, already rotting fishes — best to use a net in the open water (catfish, urchins) — and I was a fish looking up at myself (Nabokov) in a boat, reaching for me with a net...

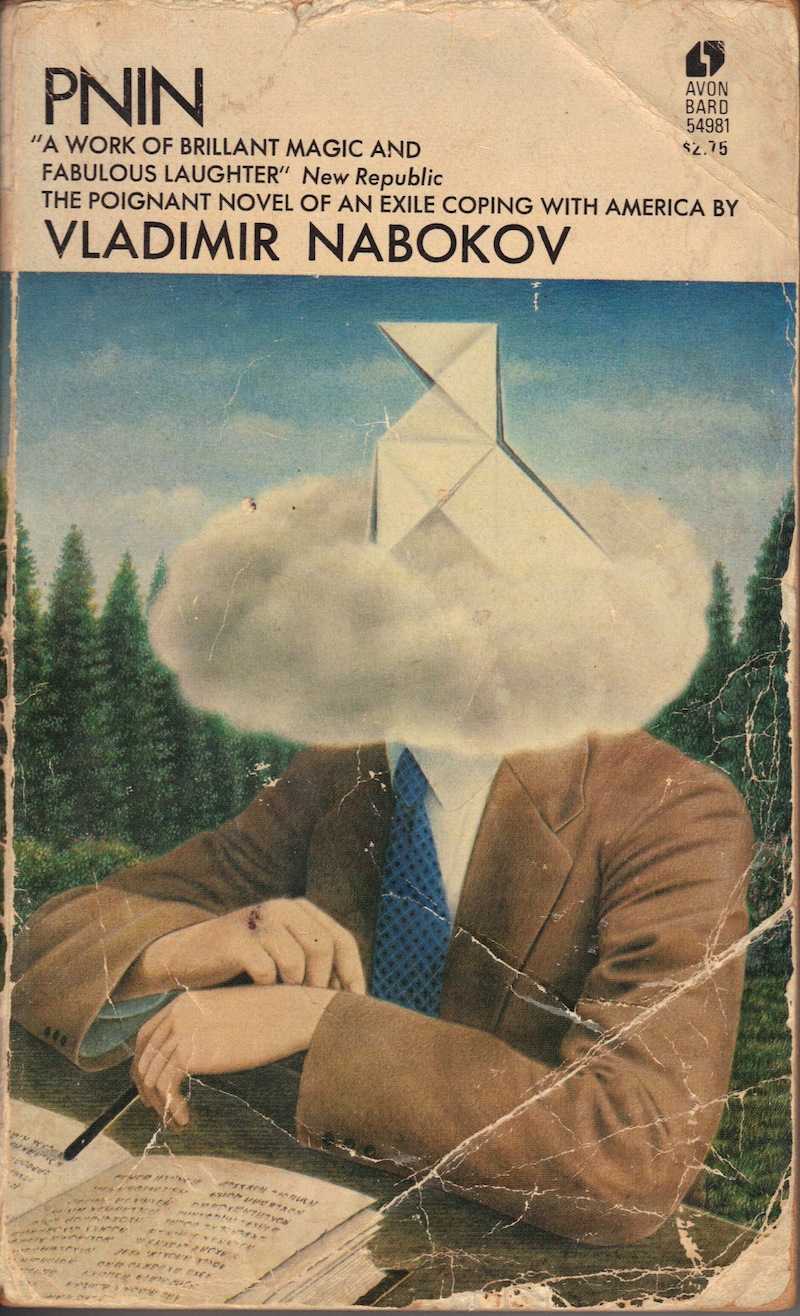

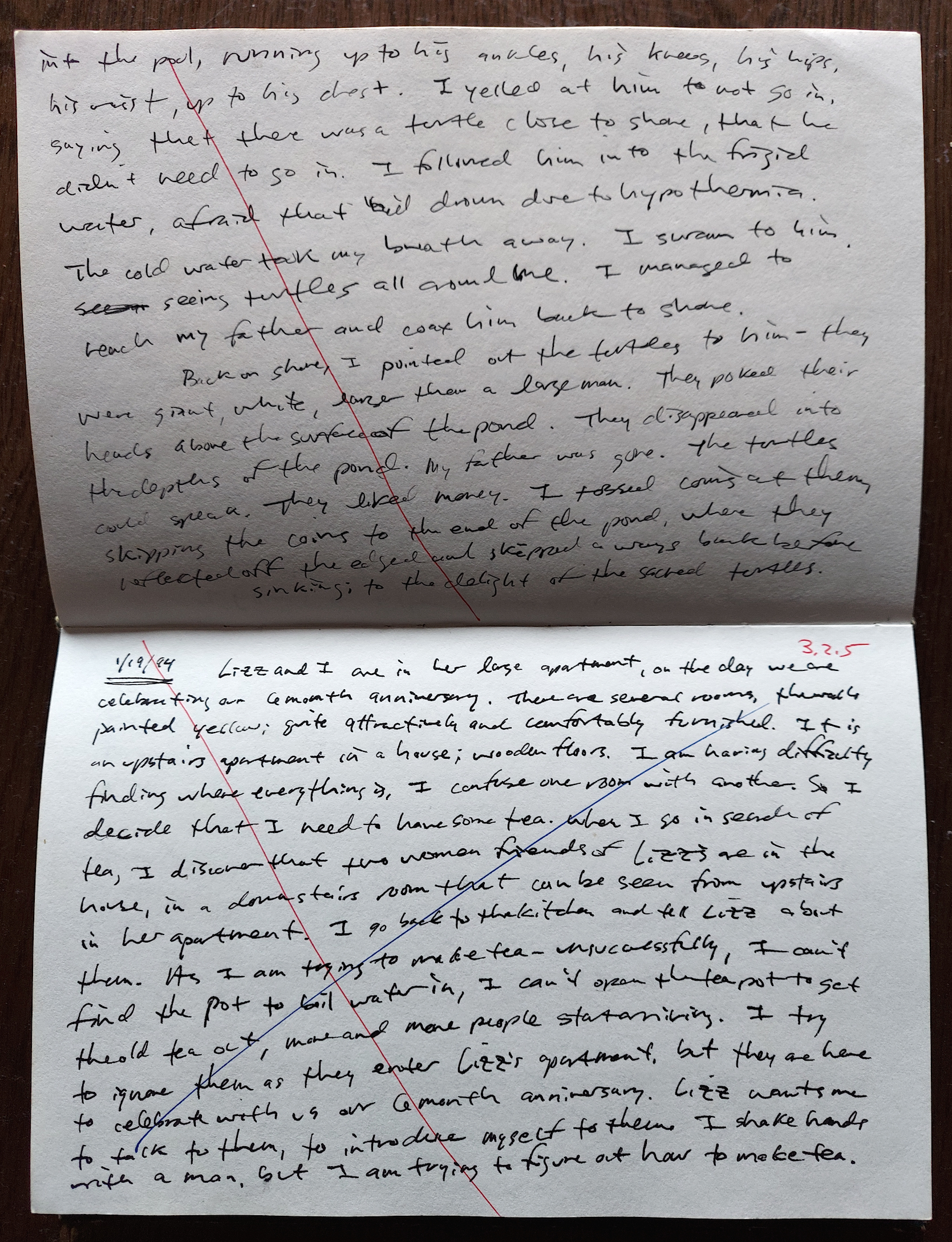

The prehistory of Nabokov’s Infernos dates from July 7, 1993, when I finished reading the first book of Nabokov’s I ever read — a battered paperback copy of Pnin found splayed on the hot tarmac where Breeze Terrace debouches into Edgewood Avenue one afternoon as I was walking from Cherrywood Road in East Austin to Les Amis café near the University of Texas campus — as well as half a year later, December 9, when, still in Austin, I dreamt the following: — I was Vladimir Nabokov, on a journey through Japan, contracted to write an article for the New York Times Magazine. I was standing on top of a slow-moving train as it rounded a bend toward a village or town. Brass handrails were built on the roofs of the train cars so that one could sight-see in the open air atop the train as it moved. The train stopped at the town. I got down off the train. I saw a woman I knew. I was surprised to see her, for she was not Japanese. I immediately split, from Nabokov, into two people: my father and myself. The woman had her young daughter, aged about 10 or 12, with her. I was the same age; my legs were thin, though shapely, I wore shorts and high-heeled shoes: my leg’s were quite similar to L’s legs. I followed my father as he walked away from the train, through a tree-lined pavilion or park. The woman, with her daughter trailing her, walked parallel to my father, but several yards away. She informed him that we were in a town in Uzbekistan or Tadjikistan. The girl and I looked at each other, but we didn’t speak. The woman disappeared. At the end of the park, through a large gate in a tall stone wall which one could not see over, could be seen a large pool or pond. My father hurried toward the pool, saying that there were rare large white turtles in the pond. He came to the edge of the pond, which was tiled with brown stones. And, though I could see a large white turtle, which I knew was a baby turtle, close to the surface and the shore, my father plunged right into the pool, running up to his ankles, his knees, his hips, his waist, up to his chest. I yelled at him to not go in, saying that there was a turtle close to shore, that he didn’t need to go in. I followed him into the frigid water, afraid that he’d drown due to hypothermia. The cold water took my breath away. I swam to him, seeing turtles all around me. I managed to reach my father and coax him back to shore. Back on shore, I pointed out the turtles to him.

They were giant, white, larger than a man. They poked their heads above the surface of the pond. They disappeared into the depths of the pond. My father was gone. The turtles could speak. They liked money. I tossed coins at them, skipping the coins to the end of the pond, where they reflected off the edge and skipped a ways back before sinking, to the delight of the sacred turtles.

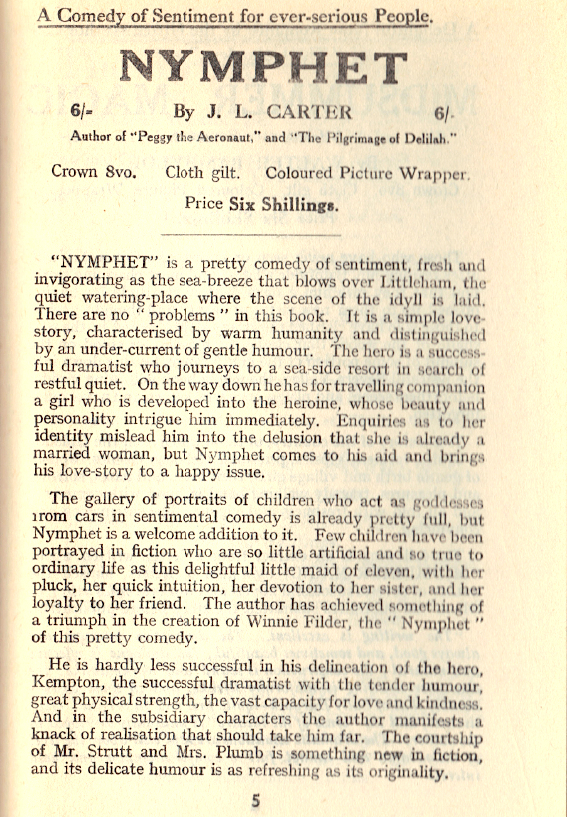

By the time Nabokov’s Infernos had evolved to the point where, in the November 10, 2008, post to the identically titled blog (abandoned after two years), I deemed it “fruitful if we conceived of Lolita as the story of a plagium (kidnapping of a child) told by means of plagium (plagiary),” it had ceased attempting to trace the (possibly) Dantesque themes ramifying throughout Nabokov’s œuvre; ceased trying to exhaustively catalogue the connections between that œuvre and the works of other writers (Woolf, Wells, Roussel, Queneau, Nietzsche, Leiris, Larbaud, Kennedy, Houssaye, Firbank, Compton-Burnett, Carter, Caine, Bourget-Pailleron, et al.);

ceased trying to determine whether those connections were intentional motifs or creative procédés on the part of the mature Nabokov (as in the well known case, not noticed until 1985 by Susan Elizabeth Sweeney, of Humbert’s “happy thought” — “Here is Virgil who could the nymphet sing in single tone, but probably preferred a lad’s perineum” — being really a riff on an entry in the Oxford English Dictionary — “1855 Singleton Virgil I 60 Who could the nymphets sing?”) or something more akin to unconscious “literary larval discs,” the Gracquian “tuf dont s’est nourrie au jour le jour, pêle-mêle et au petit bonheur, une adolescence littéraire affamée,” “les tics d’époque,” “les impressions d’enfance [...] reprises et magnifiées par la maîtrise acquise des ressources de la langue, comme les lointains incohérents de l’enfance par la chimie savante du souvenir” (Gracq 1980: 160&mndash;162) or mere figments and hopeful mirages in the cataloguer’s eye —

by that time, Nabokov’s Infernos had ceased being any sort of critical literal exercise in comparative literary criticism or “schizomythological divastigation” of “literary stealth,” and had become more a creative “laboratory” for the elaboration of my own “promiscuous textuality” as well as a motivator to read books whose existence I discovered only by means of practices engaged in in that laboratory and which, in any case, are worthwhile (both the books and the practices) in their own right.