Nabokov’s Infernos

Ahi serva Italia, di dolore ostello,

nave senza nocchiero in gran tempesta,

non donna di provincie, ma bordello!

(Dante, Purgatorio VI, ll. 76–78).

§ 1. A dream I awoke from in Paris

When I awoke from the dream of

Nabokov’s Infernos on the afternoon of February 29, 2000, I was living in the fourteenth arrondissement of Paris, not too far from gare Montparnasse, in a studio apartment on the fifth floor of 60, rue Raymond-Losserand, a zinc-roofed, red-brick building inset slightly deeper from the street than its sallower siblings making up this small

pâte d’immeubles between rue Niépce to the northeast and rue Pernety to the southwest. My small studio possessed but one window, which faced southeast, allowing me to take in a sooty abandoned bakery that sulked across the street, a fenced-off

terrain vague of rubble and weeds, and a nameless narrow cobbled lane that led to a shabby, though formerly stately building of granite, clay, and slate that seemed to lack electricity and be inhabited by an extended family of down-trodden aristocrats. The bakery sheltered a large colony of randy pigeons, who entered by a hole in the russet tiled roof, and the maps of Paris that were then current showed neither empty lot nor narrow lane, though earlier maps identified the lot as

square, and the lane as

rue,

Sainte-Léonie (later maps we may dismiss, as new apartment buildings occupy the former square, the bakery is a tall bank, and the once candle-lit squat — which is now refurbished, supplied with electricity, and occupied by wealthy Americans — is reached by a rue Sainte-Léonie that runs at right angles to its previous incarnation). Square Sainte-Léonie: I relished this spectral link to Marcel’s favorite aunt in

À la recherche du temps perdu, which I was then starting to read in French, as well as the

quartier’s having once been a Surrealist plexus, which discovery I owed, not to Breton’s portentous

Nadja, but to Queneau’s sardonic

Odile. I tended at this time to sleep until four or five in the afternoon, when I would wander out into the gloaming in search of

un café, s’il vous plaît, always choosing a sparse

comptoir of an unpopular

tabac at which to smoke a Dunhill and sip

un express, as the waiters in more frequented cafés called the demi-tasse of strong dark coffee. Often I needed a second

café noir at another counter, with two or three more Dunhills along the way, before my vision unblurred and my speech took on substance enough to be able to ask, at the third tabac,

s’il vous plaît, for another pack of

Dooneel Anternasyonal (I typically saved four or five cigarettes from the previous days’s final pack to enable me to make it to the next day’s first). With this fresh pack I ordered a beer —

un demi, s’il vous plaît. That was about the extent of my spoken French; in terms of reading, however, I was able to piece together reasonably coherent images from the chipped frescoes and gap-toothed mosaics I reconstructed from the words of Proust, Queneau, Desnos, and Perec, and was almost as depressed from the news I read in

Le Monde and

Libération as I would have been if I had been reading, say, the

New York Herald Tribune (and yet despite these lacunæ in my understanding, it was from reading

Libération that I learned, for example, that the bulk of the missiles dropped on Yugoslavia during the extensive NATO bombing campaign of March–June 1999 was thought to be unstable because of the so-called “Y2K bug,” and hence, I could hypothesize that European and American support of Kosovar independence was actually a convenient excuse to dispose of an obsolete arsenal too dangerous to keep on hand). With two coffees and a beer in me, and a fresh pack of cigarettes, I could now get down to work: recounting the previous day’s peregrinations in my daily diary; restructuring, in several notebooks and for the second or third time,

Words to Make a Story Out of;

scribbling the index-card

“ludicts” of my

Divastigations (the definite form of which I had settled on about a year earlier when, for a month after my arrival in France, I lived with my friends Kim and Ilya in Saint Mandé, an eastern suburb of Paris skirting the bois de Vincennes). Unfortunately, since the tables of most of the cafés on my route were now either set for dinner or full of convivial groups and couples of apéritif-takers, I too often skipped the first task, and, to avoid the rain, entered the first métro station I encountered, cleaved through the turnstile whose cogs I had first greased with the detachable tongue of my

carte orange, boarded the least crowded car of a train, to the line and direction of which I was indifferent, and sat down to read, and reread, Nabokov until I came to a station where I could transfer to a line — four, direction porte d’Orléans; six, direction Charles-de-Gaule Étoile; ten, direction Boulogne pont de Saint-Cloud; twelve, direction Mairie d’Issy; or, ideally, thirteen, direction Châtillon Montrouge — conducting me back to the fourteenth arrondissement, quartier Pernety, 60, rue Raymond-Losserand, through the outer gate and the front door whose code I have long since forgotten but managed to remember on more than one drunken occasion when opening a bottle halfway across Paris elided into waking naked in my sunstruck bed with no memory of traversal or transition and up five flights of stairs to my little studio apartment where I opened the window and looked out over the terrain vague at the hollow eyes of the once noble building and listened to the moaning pigeons in the bakery’s ratty

combles while I ate a small meal of pasta with sardines in tomato sauce, an apple, some cheese, washed down with a glass of cheap red wine, the rest of the bottle of which I would finish while reading and writing till dawn, when I would fall asleep and dream about reading and writing.

After writing down the dream of

Nabokov’s Infernos in my dream diary (begun seven years earlier, on May 16, 1993, in Austin, Texas), I composed a more elaborate version, embellishing the dream with details gleaned from a few hours of research on the Internet, as well as trying to flesh out some ideas for the book: —

Virgil was leading me through a hilly, winding exhibition of a Portuguese artist’s works. We stopped to examine a painting of an Italian poem reminiscent of some lines of Leopardi’s “L’Infinito”:

But sitting and regarding interminable

spaces beyond that [hedge], and superhuman

silences, and profoundest peace,

I mentally conjure a brief respite

where the heart shudders not with fear.

Ma sedendo e mirando interminati

Spazi di là da quella, e sovrumani

Silenzi, e profondissima quiete,

Io nel pensier mi fingo, ove per poco

Il cor non si spaura.

“You know,” I remarked to the author of the

Eclogues, casting doubt, thus, not just on the painting’s authenticity, but the artist’s as well, “those lines were originally composed in French, by Dante, in the ‘Bordello Scene’ (

Purgatorio, Canto VI) of his

Commedia.” And I closed the book’s cover to show him the three names of the author, translator and illustrator, then turned to a footnote where it was revealed that the trio, seeking to forge a picture that genuinely resonated with the invented artist’s unknown mother tongue, had engaged a Polish friend of theirs living in Paris to translate into Italian (since the traitor was virginal in the realm of things Lusitanian) from the alleged original in their possession, which was, in fact, nothing more than an illegitimate Englishing from which a TV at the far end of the bar was broadcasting an interview with Richard Wright: “When I won the Nobel Prize in 1943 for

Native Son, I found myself in sudden need of money, but without any. And I didn’t have but three suits. And I couldn’t borrow any, because my, because my, my, my barrister [he had meant to say “lawyer”] didn’t have any, and his didn’t have any, and his didn’t have any...”

I opened the book and turned the page to reveal a painter sitting at his easel, partially obscuring the painting he was working on, his back to us, his bearded face in three-quarter view, his hat floppy: While engaged on the royal commission to paint his famous picture which hangs in the Nardoli Gallery in Prague, “Dessert with a Danish Biscuit” (also known as “Portrait of a Spanish Fly”), the Dutch painter Jan Davidz de Heem, famous for his still-lifes, had taken time out to paint “Dante’s Bordello.”

I turned the page, peeling the painter away to show fully the painting behind: a dark scene swarming with indistinct faces; in the background, a vaguely flame-lit, doomish castle similar to the crumbling brick tower in Man Ray’s “Sade;” in the foreground, large colorful (furry?) dice accompanied by a voice-over declaiming how I’ve always had two girlfriends at a time, and which voice proceeded to reel off a long, winding Ariadne fishing line barbed with Laures and Beatrices, Natalisas and Lizesperanzas, Amandakimchiks and Cathallysons, Wisimmonieskas and Pryhatchors, Christajanines, Snowdunns and Spikelefs, at the end of which I, Dante Petrarca, was floundering, hooked,

al (in the style of)

mezzo de cammin di nostra vita

mi ritrovai per una selva oscura

che la diritta via era smarrita.

Not a dark wood, but an obscure subalpine savanna, dotted with low laurel thickets. I ducked into a nearby thicket and found at the center, a round bird’s nest containing dull brown eggs, and quickly there whirred in after me several vivacious individuals of a species hybrid between owl and peregrine, hummingbird and cuckoo. They perched on the branches in a defensive circle around the nest: gray sleek upright bodies and beaks; fierce yellow staring predatory eyes. I dashed out of the thicket and ran to take shelter in another, only to find another egg-laden nest. Afraid that its keepers would soon whirr in after me and direct their stern accusatory beaks at me, I dashed out, cradling in my arms my book,

Nabokov’s Infernos:

The trio [or triptych or trilogy] Despair-Lolita-Pale Fire represents a three-pronged frog-gig of a sort of burlesque underkill (blue bolt of lightning reveals a green glistening body impaled and twitching on black mud: and bright red streaks and puddles of pumping blood) of the Divine Comedy in which the deranged Dante — respectively Hermann, Humbert, Kinbote — guided by a bumbling and vengeful Virgil (an unsalvationable heathen, let us recall, in the spiteful eyes of Dante) — respectively Felix, Quilty, Shade (or Gradus) — tormented by the willful muse-noose of Beatrice — respectively Lydia, Lolita, Gradus (or Shade) — never attains either Purgatorio or Paradiso because he is not a mere tourist in hell, as he would like the reader and himself to believe, but is, rather, a permanent resident. The move-in date can be reckoned on the same way as Dante’s embarkation for other sights and other views in other worlds: when I found myself lost on a deceptively twisting path in dark woods, ineluctably circling back on my own frantic tracks, but not recognizing them as such:

Despair: — Hermann takes an exploratory stroll, starting from the Koenigsdorf-Waldau road at the yellow ten-kilometer post, through the woods to the lake on the shores of which Lydia’s hack-artist cousin, Ardalion, owns a plot of land where the triangle Hermann-Lydia-Ardalion had picknicked not long before, continuing on past the lake, east, through the forest (“without ever meeting a soul,” in “gloom and a deep hush”) for an hour until reaching a deserted country road, upon which another hour takes him to Eichenberg, where he boards a slow train and returns to Berlin, thinking all the while of the tramp, Felix, whom he had found, in the “dreary and barren country” outside of Prague half a year earlier, sprawled “under a thornbush, flat on his back and with a cap on his face,” on “a blurry trail running between two humps of bald ground.”

Lolita: — Humbert finds “a secluded romantic spot, a hundred feet or so above the pass where” he had left his car, a spot “where heavenly-hued blossoms ... crowded all along a purly mountain brook,” a spot where, with “the operation over, all over,” Lolita “was weeping in his arms” on the lap-robe he had spread for her, and beneath which “dry flowers crepitated softly,” a spot, alas, where he “had not reckoned with a faint side trail that curled up in cagey fashion among the shrubs and rocks a few feet” away, on which trail he “met the unblinking dark eyes of two strange and beautiful children,” “crouching and gaping,” and “the gradually rising figure of a stout lady with a raven-black bob, who automatically added a wild lily to her bouquet, while staring over her shoulder ... from behind her lovely carved bluestone children.” Back at the parking lot, “a handsome Assyrian with a little blue-black beard ... in silk shirt and magenta slacks, presumably the corpulent botanist’s husband, was gravely taking the picture of a signboard giving the altitude of the pass” (part 2, chapter 3).

Pale Fire: — Kinbote, disguised as a king fleeing his revolutionary country, follows a farmgirl-guide, Garh, and her sheepdog, along an “overgrown trail” glistening “in the theatrical light of an alpine dawn,” up a steep cliff-edge from which “a sepulchral chill” emanates, and the path “narrowed still more and gradually deteriorated amidst a jumble of boulders.” They stop to rest and the girl offers herself to him. He, homosexual, snubs her and continues on his way alone, walking “up the turfy incline,” coming to “tremendous stones amassed around a small lake,” a pool glimpsed “through the aperture of a natural vault” he had visited once or twice years ago, “a masterpiece of erosion,” and he bends his head beneath the low vault and steps “down toward the water,” in which he sees “his scarlet reflection but, oddly enough, owing to what seemed at first blush an optical illusion, this reflection was not at his feet but much further; moreover, it was accompanied by the ripple-warped reflection of a ledge that jutted high above his present position.” Fleeing King-Kinbote would have us, and himself, believe that what he saw was the reflection of one of the many red-capped and red-scarved compatriots disguised as himself, in a loyal royalistic effort to mystify his pursuers, seen from above: in “reality,” he fell to his death, and keeps falling, in perpetual revisitation to the scene of his demise (Commentary, note to line 149).

These three main threads would be supplemented by supportng filaments detailing

• the heretofore unacknowledged “shame-seizure theme” in Nabokov’s fiction — “A man having a lavish epileptic fit on the ground in Russian Gulch State Park” (Lolita, part 2, chapter 2); “There was a sudden sunburst in my head ... The wonder lingers and the shame remains” (“Pale Fire,” lines 146 and 166); “... when the dearest being I know in this world meets me in the next and the arms I know stretch out to embrace me, I shall emit a yell of sheer horror, I shall collapse on the paradisian turf, writhing ...” (Despair, chapter 6);

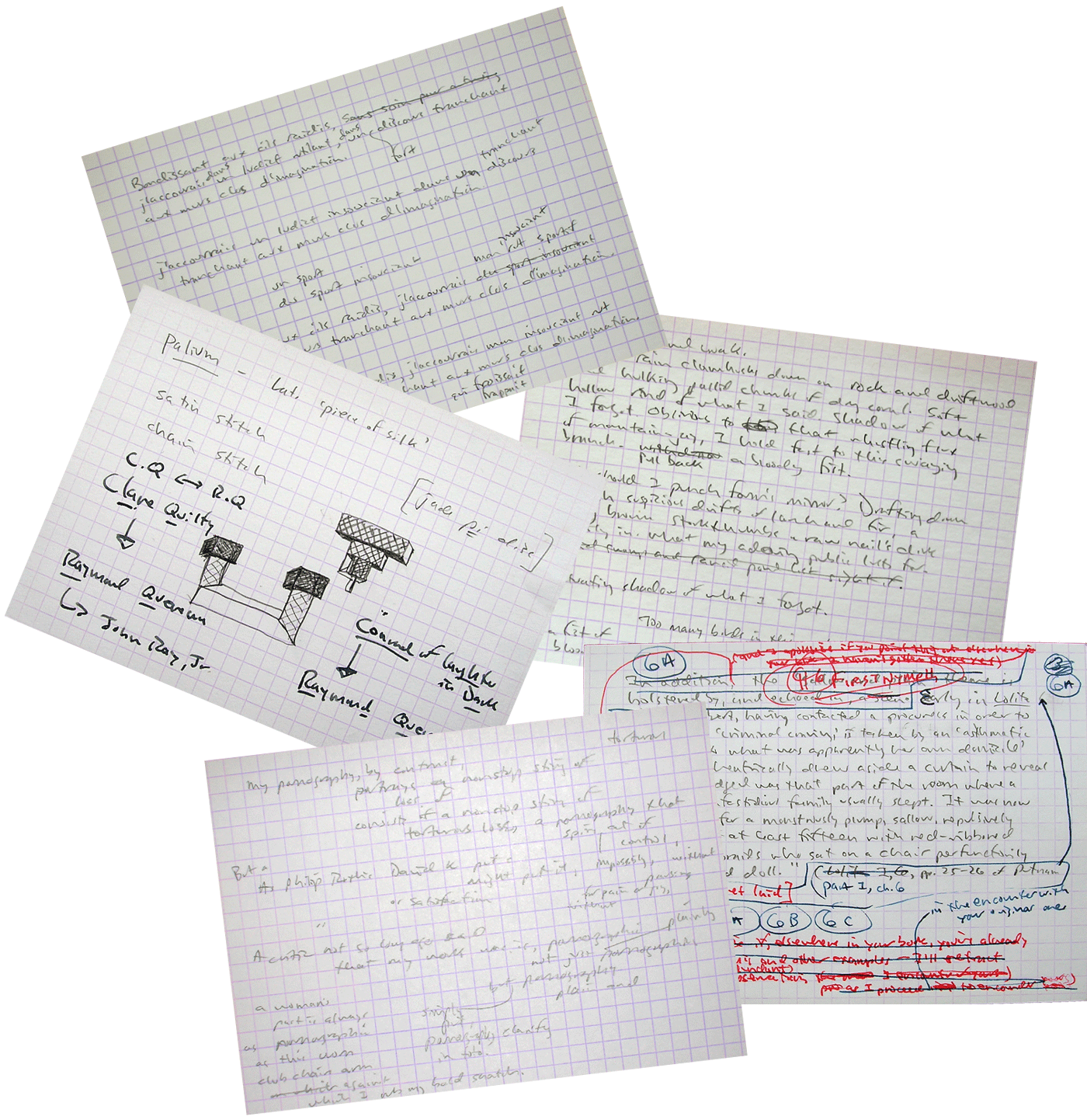

• the heretofore unrecognized “influence” of Ronald Firbank — St. Sebastian and Sebastian Knight; Quentin Comedy in RF’s Valmouth and Clare Quilty in VN’s Lolita, among others, including moths, butterflies, and other sorts of novelistic mimicry and literary aposematism;

• the heretofore undiscovered importance of the “Pastoral Fallacy” (see Pale Fire, Commentary, note to line 137);

• the heretofore unsung reliance Nabokov had on paintings for constructing certain sequences, but not plots, in his fiction — a scene in chapter 2 of Despair, for example, is a Gerard Dou painting that hangs in the Louvre;

and a few other lines and lures upon which I and/or Nabokov was or were warning the writing reader against relying too heavily, especially in those sideshow carnival piscicultural attractions wherein the only fish that can be caught are already rotting, half dead, reeled up through a narrow hole in the bottom of the wharf, and that to catch live, vibrant, breathing and avidly struggling specimens, one needs employ a net in an open boat from which I, Michael Nabokov, was bending down to snatch the squirming spiny sea urchin (whose heart is a succulent morsel) Vladimir Strickland, who was looking up from the bottom of the shallow sea at the red-capped reader who would catch him. Downy white billowy clouds soared rippling in the bright blue sun-struck sky.