Thus were it not for The Real Life of Sebastian Knight one might never have discovered the splendid novels of William Carne [sic], who wrote The Author of Trixie.

(de Jonge 1975: 526).

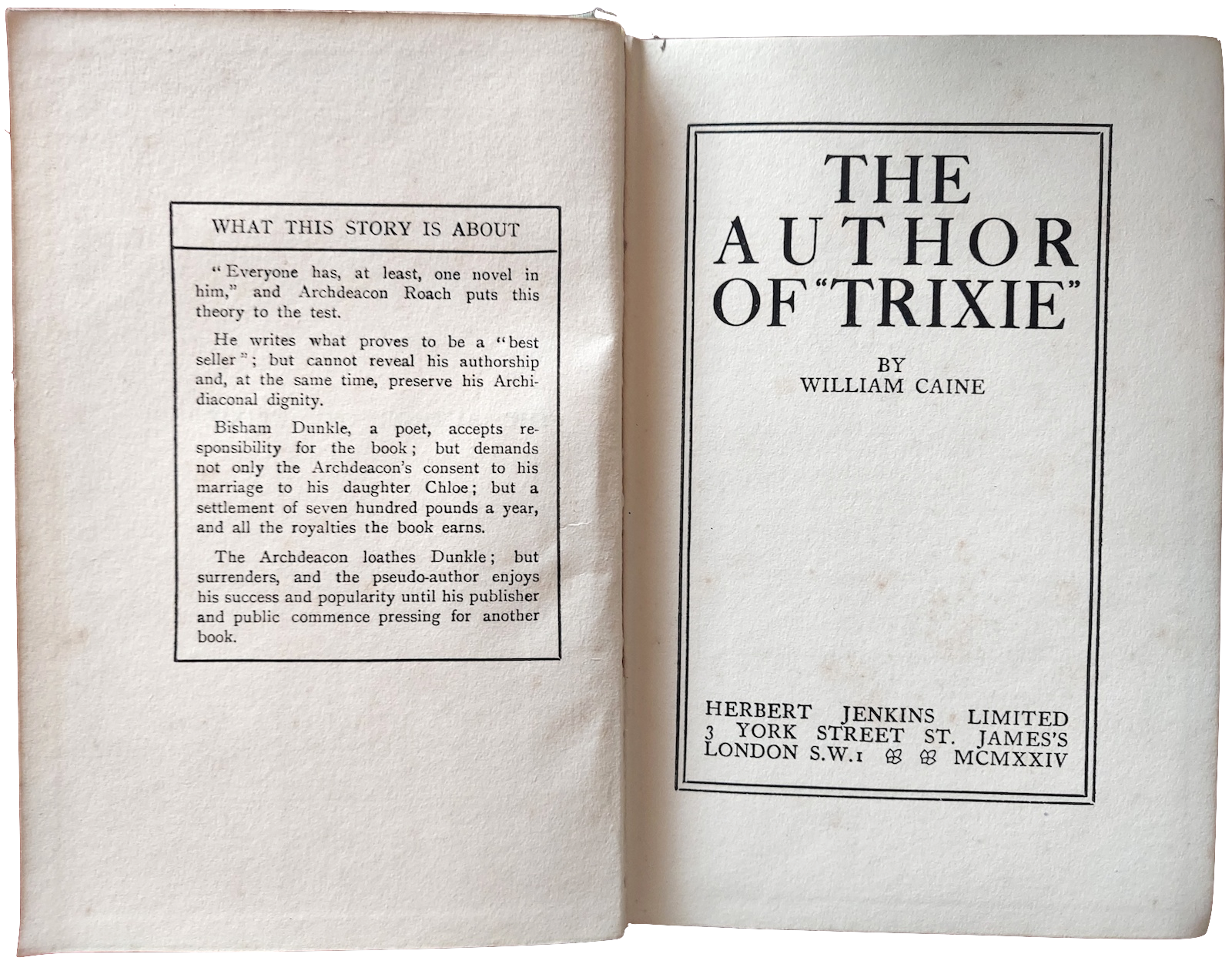

Hamlet, La morte d’Arthur, The Bridge of San Luis Rey, Doctor Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, South Wind, The Lady with the Dog, Madame Bovary, The Invisible Man, Le Temps Retrouvé, Anglo-Persian Dictionary, The Author of Trixie, Alice in Wonderland, About Buying a Horse, Ulysses, King Lear... (Nabokov 1996a: 31).The real author of The Author of “Trixie” is, of course, not William Carne, as the doubly insistent coquille in de Jonge (1975: 526; I say “doubly” since it is repeated toward the end of the same page: “Anthony Olcott has also discovered the joys of William Carne, but does not get all there is to be had from the book-list in Sebastian Knight, in an otherwise excellent study of that work.”) would have us believe, but William Caine. And although The Author of “Trixie” (published in November 1923 yet dated 1924 on the title page) is really not one of Caine’s more “splendid novels” (de Jonge 1975: 526), it, along with his last novel Lady Sheba’s Last Stunt (published in late 1924), would seem to indicate that his work, which even from his first novel Pilkington (1906) was already displaying the virtues of lightness, quickness, exactitude, visibility, and multiplicity that Italo Calvino (1988) would herald for the next millennium some eighty year later, was being propelled along the vectors of those virtues towards something potentially even lighter, quicker, more exact, more visible, more — but, alas, sudden death in Belgium at the age of 52 put paid to whatever fresh wonders of multiplicity Caine’s work might have evolved into. The anonymous reviewer in The Times Literary Supplement, however, perceived The Author of “Trixie” a bit differently:

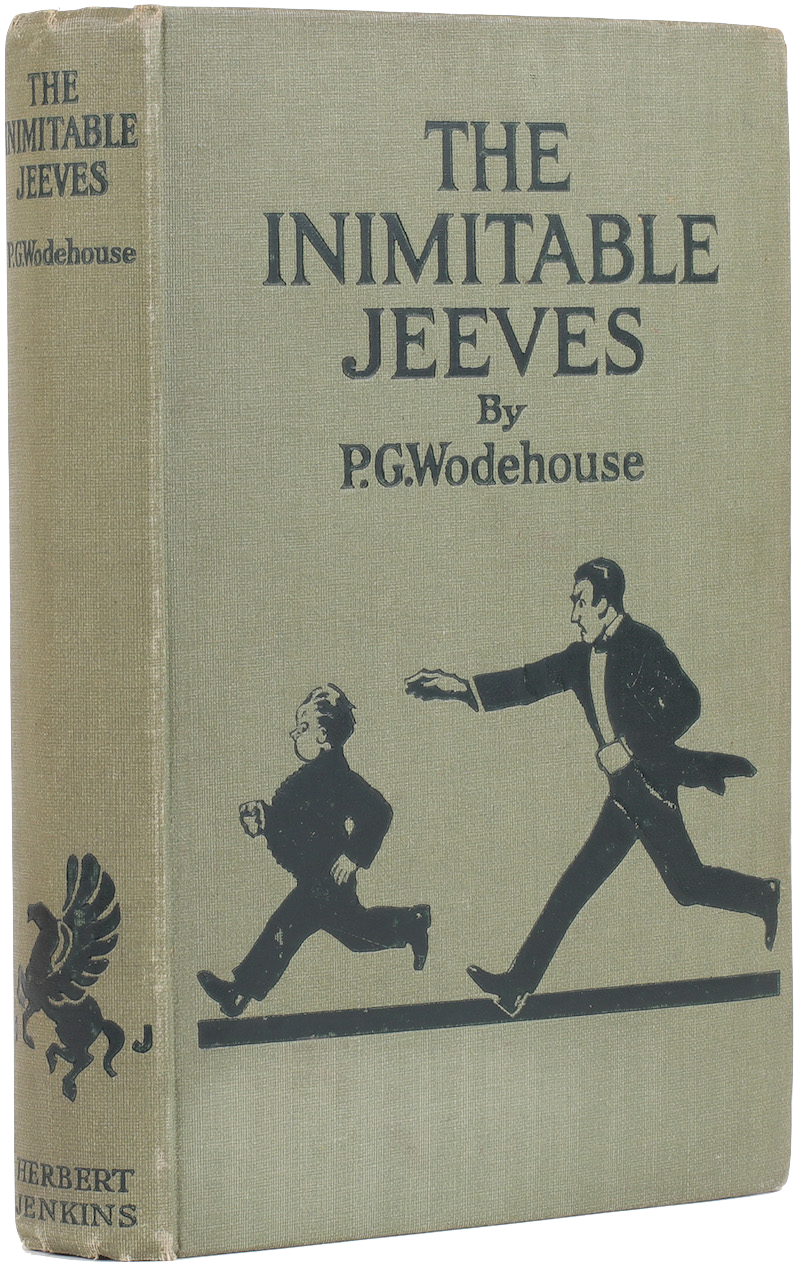

The author of “Trixie” was an Archdeacon. He wrote a novel so supremely bad that it sold better than any best seller in history. Unfortunately for him he wrote it under the name of his son-in-law, a decadent poet, who with his wife, a detestable young woman, proceeded at once to blackmail him and to batten on his royalties. There followed a rather long-winded and elaborate game of bluff between the two sides which ended in the Archdeacon being made a Bishop and renouncing all claims to the fame and the interviewing and the photographs in the illustrated papers for which he had so pathetically pined. The story, so intentionally preposterous, should be written lightly and pleasantly, and that is where Mr. Caine fails. (TLS, November 8, 1923: 752).To me, The Author of “Trixie” seems hardly more long-winded, and quite a bit lighter and pleasanter, than a more well-known book published around the same time by the same publisher, P. G. Wodehouse’s The Inimitable Jeeves, the brief review of which in The Times Literary Supplement runs as follow:

Mr. P. G. Wodehouse has claims to a good position among our writers of the very lightest fiction. In this series of stories, having for their centre Jeeves, the gentleman’s gentleman to Bertie Wooster, the usual young man about town, we have a favourable specimen of his art and method. The stories are probably better in magazine than in volume form. Here the fun verges on monotony. (TLS, May 24, 1923: 358).Where Wodehouse’s monotonous “art and method” contents itself with indulgent winks and knowing tickles, Caine’s rollicking polypotent instrument of parody contends — ever so deftly that the patient, still ignorant of the malady, often remains oblivious too of the slice — with the rottenness beneath the superficial foibles of those gentlemen’s gentlemen and other usual young men and women about town, by not merely poking fun at, but sardonically teasing, mocking, prodding, flaying, and laying bare the hypocrisy, the corruption, the venality, the bigotry propping up the staid mansions and decorous manners of the gentle gentiles of the British Isles. Even the “amusing situations and irresponsible fun” of Lady Sheba’s Last Stunt are not without their sordid sides — the threat to expose them versus the attempt to keep them hidden being, of course, a guiding motif of the book — and I’m curious as to what the brief review on page 828 of the December 4, 1924, issue of The Times Literary Supplement had to say on the matter, but, unfortunately, in the only pdf of the issue in question I’ve been able to find in the databases, the relevant page has been replaced by a doublet of the preceding page.

About Buying a Horse was written by Sir Francis Cowley Burnand; its chess application is obvious. Caine’s The Author of Trixie is about an archbishop who secretly writes a frivolous novel (thanks, Professor Boldino). (Olcott 1974: 106; italics in original).The real fictitious author of “Trixie” is, of course, not an archbishop, but an archdeacon, who, to avoid jeopardizing his chances of being promoted to bishop, does not follow his archidiaconal conscience — “the Pastor of Souls,” that part of himself is soon called — and “suppress by fire the bright creature of his fancy,” produced after five months of “clandestine and therefore exquisite” “dallying with the Muse,” but is swayed instead by the reasoning of a new aspect of himself — “the Artist (whom he had happily discovered within him)” — “to give it to the world” (Caine 1924: I, (4), 15–19) — but how? After the Pastor of Souls dismisses the Artist’s first two suggestions — “Anonymity was just as dangerous as pseudonymity.” “To adopt an alias is to set everybody to the work of discovering whom it conceals; and sooner or later the truth is ferreted out.” “Sooner or later, sooner or later, the cloak of anonymity was sure to be torn away.” — he suggests a third way: “‘Do,’ said the Artist, ‘as Bacon did. Get a Shakespeare’” (Caine 1924: I, (4), 20–21). Perhaps Olcott’s informant conflated the clerical rank of the author of “Trixie” with the name of that author’s “Shakespeare,” Bisham Dunkle? And perhaps the novels of Caine which de Jonge discovered are splendid in the way Caine means the word in his Great-Snakes! of 1916, to refer to an entity rather less joyous or joyful and much more self-righteous, condescending, and hypocritical:

In a terse note in the Library of America version of The Real Life of Sebastian Knight, Brian Boyd remains strictly bibliographical concerning the eleventh item in the list of books — “The Author of “Trixie” (1923), comic novel by William Caine (1873–1925)” (Boyd 1996: 676). — but a few years later more expansively lauds that comic novel in a post to the NABOKV-L on May 30, 2000:“Your mother,” said Mr. Wildbore, “is a splendid woman. She is President of twenty philanthropic societies.”

“We can do no good discussing mamma,” said Isabel. “But don’t I hear her calling for you?”

“She has discovered,” cried Mr. Wildbore, and darted out through the French window.

“I wonder what he means,” thought Isabel. (Caine 1916: XI, 137).

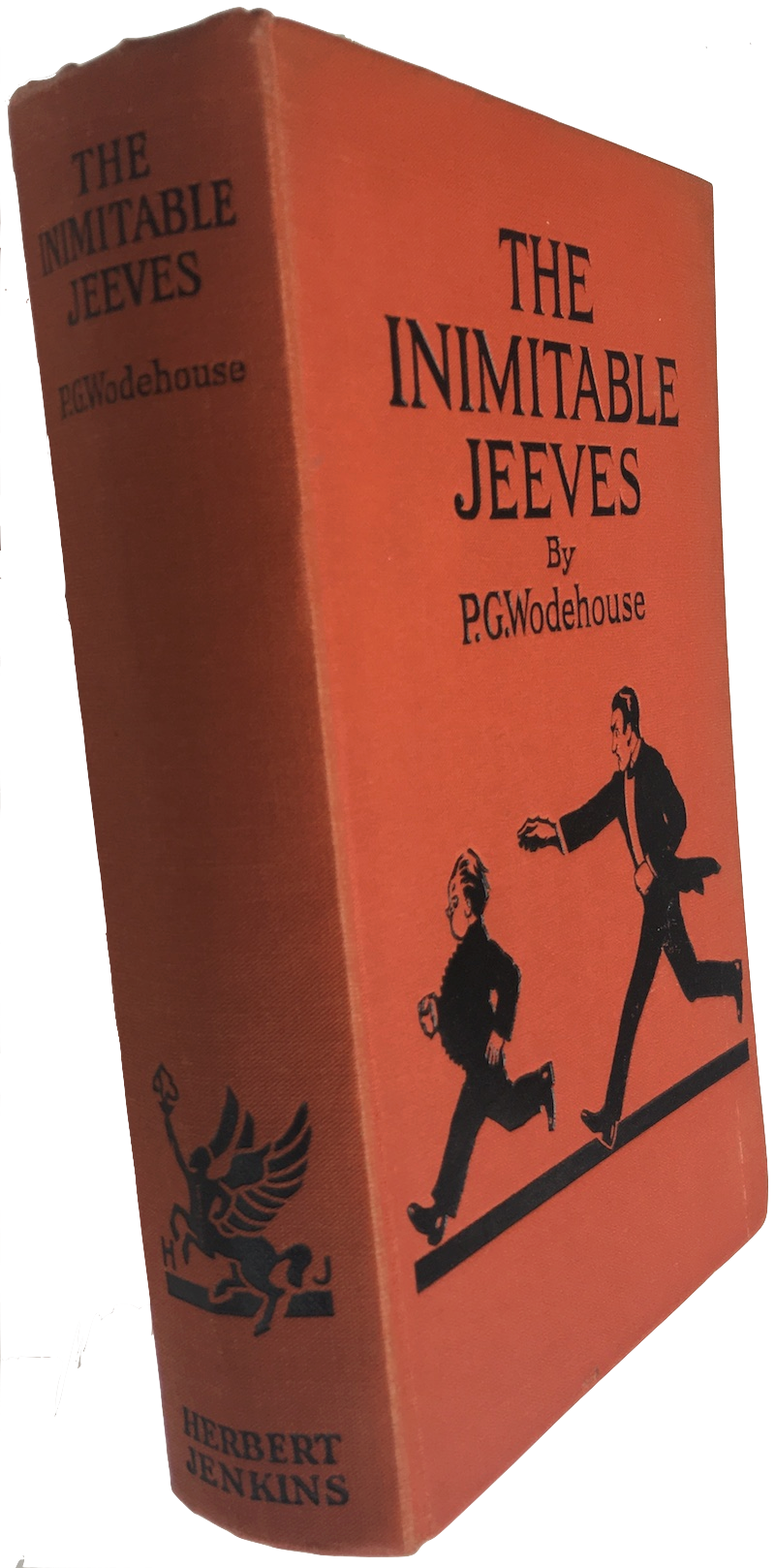

In a May 24 posting Jeff Edmunds correctly identifies William Caine’s “The Author of Trixie” (1924) and Sir Francis Cowley Burnand’s “About Buying a Horse” (1875) on Sebastian Knight’s bookshelf, and adds: “One wonders what relevance these might have had for Sebastian Knight.” I wonder too about Burnand’s book, unless its Victorian humor seems teeth-grindingly bad to Sebastian, but Caine’s novel is a little masterpiece that all lovers of Nabokov should seek out. Wonderfully deft and wrily self-consciousness in a way quite surprising for its time or at least (since this was, after all, post-Ulysses) for its time and tone. Once you read it, you’ll see its comic relevance to Sebastian Knight, who could almost have written it. (Boyd 2000).Apropos of that horse in the title of Burnand’s book (which Olcott relates to a chess knight rather than, say, to the burning of letters and manuscripts), a horse which is clearly visible, winged, on the spine of Caine’s The Author of “Trixie” — this winged horse, this Pegasus, also occurs on some exemplars of the Herbert Jenkins first editions of P. G. Wodehouse’s books, but evolves in later printings into what looks like a winged centaur holding aloft a torch, Caine’s books apparently remaining innocent of this chimerical transformation, either because they did not sell enough to warrant subsequent printings, or he did not live long enough to publish new novels with the same publisher bearing the changed logo. The caricature of himself as one of the members of the Committee of Authors, Sir William Keyne, O.P., L.S.W.R., that he includes in The Author of “Trixie” is perhaps not entirely irrelevant here:

Sir William Keyne came bustling forward, a thing he could always be trusted to do. “Now, my dear Archdeacon,” he said, “we’re all present and ready to hear what you have to say. So this is your son-in-law, Mr. Dunkle, is it? I am Sir William Keyne, the novelist. It gives me very great pleasure to meet you, Mr. Dunkle, though I don’t happen to have read either of your books. You see, as a member of the Worst Sellers’ Dining Club, I am precluded by my oath from reading any work of fiction which sells more than three hundred and fifty copies in Great Britain. Nevertheless —”Nor are the following two passages from The Real Life of Sebastian Knight, the second from a fictional letter to the publisher Sebastian snubs in the first:“Oh, shut up,” said Chloë. At the same moment she drove the point of her parasol vigorously into the ribs of Sir William. “Now then, Venerable,” she went on, while Sir William fell back gasping and clutching at his side, “which is it to be — Peace or War?” (Caine 1924: XVII, (1), 233–234).

It appears that in Sebastian’s first book (1925), The Prismatic Bezel, one of the minor characters is an extremely comic and cruel skit upon a certain living author whom Sebastian found necessary to chastise. Naturally the publisher knew it immediately and this fact made him so uncomfortable that he advised Sebastian to modify the whole passage, a thing which Sebastian flatly refused to do, saying finally that he would get the book printed elsewhere, — and this he eventually did. (Nabokov 1941, 1968: 6, 54).

“But even if there were such a thing as a ‘literary career’ and I were disqualified merely for riding my own horse, still I would refuse to change one single word in what I have written. For, believe me, no imminent punishment can be violent enough to make me abandon the pursuit of my pleasure, especially when this pleasure is the firm young bosom of truth. There are in fact not many things in life comparable to the delight of satire, and when I imagine the humbug’s face as he reads (and read he shall) that particular passage and knows as well as we do that it is the truth, then delight reaches its sweetest climax.” (Nabokov 1941, 1968: 6, 55).As I ponder this neat coincidence of a fictitious book by a fictional author intent on riding his own horse being published the same year that the real author of The Author of “Trixie” died unexpectedly at the age of 52 while on holiday with his wife in Belgium; as I recall the oneiric Humbert Humbert “dutifully bobbing up and down, bowlegs astraddle although there was no horse between, only elastic air — one of those little omissions due to the absent-mindedness of the dream agent” — in the wake of “big Haze and little Haze [riding] on horseback around the lake” (Lolita I, § 11, 56); as I look at the rearing Pegasus and the reaching Centaur on the spines of those books published by Herbert Jenkins — I think that what I mean by the term “schizomythology” in the subtitle of Nabokov’s Infernos can begin to be sketched out by reflecting on the images of those chimeras as well as on Calvino’s discussion of Medusa, Perseus, and Pegasus:

The relationship between Perseus and the Gorgon is a complex one and does not end with the beheading of the monster. Medusa’s blood gives birth to a winged horse, Pegasus — the heaviness of stone is transformed into its opposite. With one blow of his hoof on Mount Helicon, Pegasus makes a spring gush forth, where the Muses drink. In certain versions of the myth, it is Perseus who rides the miraculous Pegasus, so dear to the Muses, born from the accursed blood of Medusa. (Calvino 1988: 5).And I also think of one of the incidents the fictional author of the fictitious novel in Caine’s The Strangeness of Noel Carton (of which the titular protagonist is possibly the source for the double typo in de Jonge [1975]) contrives to win for his textual alter ego the gratitude of the novel-in-a-novel’s heroine:

Hilda and Ronald had almost reached the gate that leads into Knightsbridge. They were riding very close together. And so, when the wind picked up a big sheet of newspaper and swept it suddenly across the very eyes of Hilda’s horse, Ronald’s came in for the same amiable attention. He rose, accordingly, straight up on his hind legs, and after pawing the air madly for a few seconds fell heavily on his side. Meanwhile Hilda’s big, black, fidgetty beast had whirled round and bolted, head down, eyes staring, blind and mad with terror. He came thundering down the roadway with Hilda, sitting him like a rock and doing her best; but she might as sanely have hoped to hold a battleship with a string as to pull the beast up by hauling on his mouth. He was away, and until he should run his fright out of him or come to some everlasting smash, Hilda had nothing to say to it, nothing whatever. (Caine 1920: 129).But to return (while letting that horse run out his fright) to the comic novel in question: The novel’s “Bacon,” that is, the author of “Trixie,” in the form of the big burly archdeacon Samson Roach, who contains within himself the two persons of Pastor of Souls and Artist, can only persuade tall delicate Bisham Dunkle, peerless ballroom dancer and self-published author of two collections of little poems, to be his “Shakespeare,” on the condition that the former consent to the latter marrying Chloë, the fifth of the former’s “bouquet of daughters [...] just turned seventeen” (Caine 1924: III, (2), 39), and that the archdeacon settle seven hundred pounds a year on her, plus a minimum of five hundred pounds’ worth of furniture. And Dunkle is only able to save face with his new bride Chloë — “‘Well [she chides him on learning the disappointing news that not only is “Trixie” a work of prose fiction rather than a narrative poem, but he’s to receive a five hundred pound advance and twenty per cent. royalty rising to thirty for it], if I were to write a mordant burlesque of the hogwashiest kind of sloppy feuilleton, I should have to call it “Trixie”’” (Caine 1924: IV, (3), 67–69) — by convincing her that he wrote “Trixie” entirely for her sake — “A girl like you requires a setting that nothing under seven thousand a year can provide” (Caine 1924: IV, (3), 68) — and as a burlesque. Now, despite having “taken Boyd’s advice to heart and read Caine’s The Author of ‘Trixie’” (Johnson 2003) — and despite de Jonge’s insight that “a conception of art as pattern and balance also accounts for Nabokov’s love of parody. He sees the spirit of parody as being close to that of poetry itself. Time and again his best work has a faintly parodistic basis; Shade’s poem, or the way that the apparently straight narrative of Lolita is undermined by literary allusions” (de Jonge 1975: 526) (literary “allusions,” of course, far from “undermining” Lolita, are the book’s very texture) — even someone like D. Barton Johnson, editor of the NABOKV-L, ignores this “faintly parodistic basis” common to both Caine and Nabokov, and seems to see in The Author of “Trixie” nothing more than a “lightheartedly nasty” comic novel of manners without “much literary merit” or “thematic tie” with The Real Life of Sebastian Knight, viz.:

Although I am not so enthusiastic as Brian (and sincerely hope that it was not written by Sebastian), I too see why VN might have put it on Sebastian’s shelf. It is a tale of misrepresented authorship — a theme that likely lies at the heart of RLSKn. The novel is replete with allusions to Bacon and Shakespeare. (And also to those earlier English clergymen who wrote scabrously funny works, Swift and Sterne. These do not figure in VN’s book, so far as I recall.) (Johnson 2003).After a providing a curtailed bibliography of Caine and reproducing the publisher’s blurb “What This Story Is About” facing the title page, Johnson continues with a synopsis of The Author of “Trixie”, carelessly confusing, à la Olcott, archdeacon and archbishop:

Poetaster Dunkle and Chloe quickly run through their new wealth and scheme to force her father to write a second book to be credited to Dunkle. If he refuses, they will expose him as the author of “Trixie.” The new book is soon ready but the Archdeacon decides that whatever the cost he wants the glory of authorship for both “Trixie” and the new work. The young couple, whose scheming is now taken over by Chloe, an even nastier number than her husband, agree to the author’s demands but plot to steal the manuscript and have the Archbishop hijacked to a three year trip on a South seas whaler (assuming he will cave in ere it happens). Archbishop [sic] and daughter exchange dastardly bluff and counterbluff until the matter is resolved when Trixie’s author is named a bishop and must choose between literary glory and ecclesiastic position. The novel is lightheartedly nasty and all good fun with “a happy ending”. (I am always bemused that the very idea of “a happy ending” is so alien to Russian readers that they use the English term “Hepi end” to describe it.)Judging by the numerous novels advertised at the back of “Trixie” the book’s publisher, Herbert Jenkins Limited, specialized in (very) light fiction — adventure, spy, murder mystery, and social comedy. The only “name” author, I recognize, is P.G. Wodehouse.

Nabokov’s use of Caine’s 1924 novel is instructive in another sense. In my investigations of VN’s readings of contemporary (to him) British literature, I tend to assume that his contact with current stuff largely ended when he returned to the Continent after finishing Cambridge in June 1922. Unless “Trixie” appeared in serial form prior to that date, VN must have read it in Germany. (There was a 1924 German translation, but it seems unlikely VN would have read it.)

As much as I would like to see some deeper thematic tie between “Trixie” and RLSK (and among the entire list of titles), I cannot. Nor do I find Caine’s novel to have much literary merit. It compares very badly with Norman Douglas’ 1917 “South Wind” a comic novel that also appears on Sebastian’s shelf and that Nabokov is known to have admired. (Johnson 2003).

In a review of some books about Nabokov in the May 16, 1975, issue of The Times Literary Supplement, Alex de Jonge writes, “Were it not for The Real Life of Sebastian Knight one might never have discovered the splendid novels of William Carne [sic], who wrote The Author of Trixie.” De Jonge continues to temper his enthusiasm with a typo later in the same piece: “Anthony Olcott [on page 106 of A book of things about Vladimir Nabokov] has also discovered the joys of William Carne [sic], but does not get all there is to be had from the book-list in Sebastian Knight, in an otherwise excellent study of that work.” What are the “joys” Olcott discovered in Caine? No more than this: “Caine’s The Author of Trixie is about an archbishop who secretly writes a frivolous novel (thanks, Professor Boldino).”